California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

Anthony Zhang

Image Credit | polarbearstudio

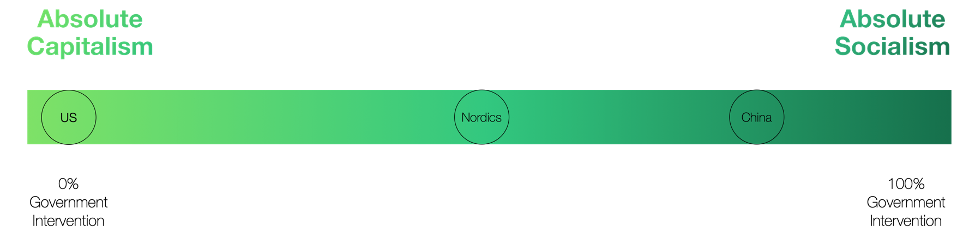

The Nordic countries may be operating less like pure capitalistic economies. Their social institutions reflect a mixed-market economy that blends free-market principles with significant government intervention.1 Capitalism and socialism may not just be monolithic. The two systems represent opposite ends of an “institutional spectrum:” at one extreme, capitalism is marked by a complete absence of government intervention or state control, while at the other, socialism is featured by total government involvement in economic affairs (see illustration 1). Every country falls somewhere along this spectrum, and most are shifting their position on it continuously to meet evolving national needs. The Nordic countries likely drift somewhere in the middle.

Robert Strand, “Global Sustainability Frontrunners: Lessons from the Nordics.” California Management Review, 66/3 (2024): 5–26.

Illustration 1:

As Americans look at the Nordic model and explore possibilities of moving toward the midpoint to bring their high economic productivity, strong social equality, high levels of social trust and personal happiness back home,2 several cultural and social challenges remain. First, overconsumption is deeply ingrained in American culture. This is not just the result of individual choices, but of the structural systems that encourage excessive consumption. In her research “Overconsumption as Ideology,” Professor Diana Stuart argues that overconsumption is a necessary and secondary byproduct of capitalist production, and achieving sustainable consumption requires structural changes in our political-economic system.3 According to the U.S. Environmental Footprint Factsheet from the University of Michigan, it would take over five Earths to support the global population if everyone consumed like the average American.4 Yet, any structural changes that could undermine current growth-centric business models will face strong resistance from industries and stakeholders, as most corporations play a central role in promoting overconsumption to sustain business growth and maximize profits.

Second, American consumer patterns are heavily shaped by built environment. Consider a comparison between Copenhagen and San Francisco. Copenhagen has a strong bicycling culture, with a large portion of residents using bikes for their daily commute. According to the City of Copenhagen’s Bicycle Account, 62% of residents commute to work or school by bike.5 In San Francisco where bike lanes are also extensively available, only about 4.2% of commute trips are made by bicycle.6 In much of California, it’s nearly impossible to get around a city or town without a personal vehicle. Additionally, in San Francisco, around 70% of households own or lease a car,7 and nationally, 91.7% of U.S. households have at least one vehicle.8 This widespread car ownership is largely driven by the country’s expansive geography and suburban sprawl. While there have been efforts in San Francisco to redesign cities to better support public transportation and cycling—ultimately aiming to reduce overall consumption—its deeply entrenched car-centric urban design continues to pose challenges, facing resistance from drivers, businesses, and the automobile industry.

Finally, the most significant difference lies in cultural and racial diversity. Denmark and its neighbors in the Scandinavian region are highly homogenous. In Denmark, 86% of the population is ethnically Danish, sharing deep ancestral roots with Northern Germans.9 Other Nordic countries also have populations where over 80% belong to the same ethnic group. This level of racial homogeneity often correlates with a collectivist culture and makes consensus-building relatively easier—a stark contrast to American society. This observation aligns with my personal experience living and working in Japan for 7 years, another highly homogenous society where 98% of the population being ethnically Japanese.10 Like Japan, the Nordics place a strong cultural emphasis on agreement, consensus and social harmony over confrontation. As a result, the Nordic countries benefit from their high levels of cultural cohesion and shared mindsets, facilitating consensus-driven policymaking, effective public-private partnerships, and cooperative labor relations. In contrast, the US—with its rich racial, cultural, and ideological diversity—while emphasizing respect and celebrating individual differences, faces greater complexities in achieving collective compromise and building national consensus, which in turn makes it more challenging to foster social cohesion and coordinated productivity.

Despite all the challenges, what can the US learn from the Nordics? The first suggestion would be encouraging stakeholders to rethink their perspective on capitalism. The Rambøll Foundation offers a great example for deep dive. One key area is their use of remaining profit—that is, how best to use profits once operating costs are covered. Rambøll Foundation owns 96.9% of Rambøll Group A/S, with the remaining shares held by employees through an employee share scheme.11 This ownership model reflects the Foundation’s vision of building a company where profits are reinvested in long-term development and where employees have a real stake in the company’s success. The Foundation also directs a portion of profits toward multiple philanthropic efforts. In 2023 alone, it donated DKK 28 million to sustainable development initiatives such as regenerative rebuilding, improvements to the built environment, and better resource management.12

Another example is IKEA Social Entrepreneurship B.V. As the philanthropic arm of Inter IKEA Group (See illustration 2), its operations are funded through internal corporate funding, as well as strategic partnerships and reinvested returns from its initiatives. According to Lisen Wirén, Program Manager at IKEA Social Entrepreneurship B.V., it is internally considered a strategic initiative, aligned with the company’s long-term mission to be “People and Planet Positive,” supporting social enterprises through funding, accelerator program development, and impact investments.13 IKEA Social Entrepreneurship focuses on supporting social entrepreneurs who are developing innovative solutions to scale their social impact. Since the start of this program, they have supported about 200 social enterprises in 35 countries, with more than 370 co-workers contributing as mentors or coaches in six accelerator programs.14

Illustration 2:

This is not to suggest that all companies should transform into philanthropic foundations like Rambøll or replicate IKEA’s social entrepreneurship model. However, can we at least rethink and reevaluate the infinite profit maximization, growth-centric capitalism? While this model has driven remarkable innovation and economic prosperity, does it also contribute to widening social inequalities—disproportionally benefiting a small segment of society at the expense of the broader public interests and even those of future generations? Can corporate leaders revisit their profit redistribution strategies, thoughtfully identify social issues that align with their company’s long-term growth, and invest a portion toward social initiatives? Sustainable capitalism is not just about “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”15 More urgently, it must also address the needs of a broader audience, including the marginalized and disadvantaged communities in our current generation; thereby, a form of capitalism that can be sustained into the future.

Insight

Seojoon Oh

Insight

Seojoon Oh

Insight

Swetha Pandiri

Insight

Swetha Pandiri